Capsular contracture is the medical term that describes an excessive amount of scar tissue around a breast implant. This scar tissue leads to hardening and/or displacement of the implant. Current statistics report that approximately 3% of implants, regardless of kind, can elicit the formation of excessive scar tissue around the implant, which leads to contracture of the capsule. The capsules are classified as follow: Grade I, minimal amount of scar tissue that allows the implant to be soft as they are meant to be; Grade II, moderate amount of scar tissue that makes the implant to feel firm; Grade III, severe amount of scar tissue causing deformity and/or displacement of the implant; Grade IV, severe amount of scar tissue causing hardening of the implant combined with pain. Grade III and IV capsular contractures need surgical intervention to be resolved. For the sake of patient education, before choosing this kind of surgery, it is useful to discuss a brief history of breast implant surgery.

The implants that were successfully used in patients were first described Cronin and Gerow (1964). The silicone gel-filled Silastic envelope breast implants manufactured following these doctors description soon underwent several modifications. The Simaplast implant was described by Arion (1965) and consisted of an inflatable silicone bag that could be inflated with different fluids among them saline. The saline implants as we know now where born. Soon after these silicone implants (filled with silicone gel or saline fluid) started to be placed in patient’s breasts, a not uncommon complication was observed. Large numbers of patients, in various studies ranging from 30% to 50%, sooner or later were developing capsular contractures of the breasts. Obviously, as soon as this complication was described, the reasons for its occurrence and solutions to the problem started to be investigated. It should be noted that the first manufactured silicone gel breast implants had 3 small round patches of Dacron (similar to these days Velcro) incorporated onto the posterior side of the implant.

The idea was that the patches would stimulate the formation of enough scar tissue for the implant to stay in place preventing the sagging of the breast. Those patches also prevented movement of the implants, so the first solution to the problem of contracture formation was to remove these patches, in order to allow the implant to move freely within the pocket and avoid decreasing the size of the pocket. It was thought that a larger pocket would prevent constriction of the implant by scar tissue. In addition to that, it was suggested that the implant pocket itself needed to be made “larger,” and the patient needed to strongly massage the implant after surgery, again with the idea of preventing contraction of the scar tissue (i.e. the capsule around the implant). Another theory proposed at that time as to why contractures occurred was accumulation of blood from the procedure, so many surgeons started to add drains during the surgery, as well as applying hard and very compressive postoperative bandaging to expand the implant too. Unfortunately, removal of the Dacron patches, enlargement of the pockets and postoperative massage solved the problem. The next solution that was popularized in the 1970s was surgical revision of the operation, opening the implant capsule around in order to enlarge the pocket, or even performing what was called “closed capsulotomy,” in which the patient was given some sedation, and the implant was squeezed hard enough to provoke rupture of the capsule and subsequent softening of the implant.

This treatment fell short of being the solution as well since the capsules recurred soon after these procedures. In the 1980s studies that demonstrated the migration of the silicone gel through the implants silicone wall. Doctors and scientists theorized that the silicone gel inside the implant migrating through the envelope of the implant, (a process called leaching (“bleeding out”), was the cause of the inflammatory process leading to the formation of a thick scar tissue capsule around the implants. In an attempt to solve the problem, implants were then manufactured with thicker shells and even with double shells, to prevent migration of the silicone through them. Unfortunately, this new generation of implants did not provide a solution for all patients, even though it appeared that the incidence and chances of developing a capsular contracture decreased in frequency.

The same interchange of the implant content and the surrounding tissues happen with the saline filled implants. Even though the saline causes no inflammatory process on this tissues this implants did not completely eliminate the patient’s chances of developing a capsule. Another problem with saline implants is that they have a tendency to develop wrinkles at the edges, and the wrinkles were visible on thin patients, so when surgeons tried to use them on top of the pectoralis muscle, the results were really poor.

A milestone in Breast Implant Surgery Miami was reached when the submuscular plane was used for placement of the implants (i.e. the implant was placed in a pocket created under the pectoralis major muscle). With that simple maneuver of inserting the implant under the muscle, the incidence of capsular contractor decreased substantially. It was felt that possible explanations for this improvement could have been that the muscle provided good blood circulation around the pocket, and that the muscle itself was constantly massaging the implant as the patient moved her arm. Even though the capsular contracture rate declined, a solution was still needed to treat the patients who did unfortunately develop these unwanted complications.

In 1995, a California company called “Même” developed a new silicone gel implant that has a polyurethane cover outside. This implant was extremely successful to treat patients with capsular contractures. The polyurethane covering the implants, which was providing a layer of “spongy” material, was inducing the growth of scar tissue that created a capsule in and out of the pores. By doing so, the capsule surface enlarged considerably, because it was not a smooth capsule anymore and a rough capsule going in and out of the pore was being developed. The theory was that the collagen fibers that form the capsule and have the ability to contract (like muscle, in a way) were not be able to harden the implant. Another explicative idea was that it was the polyurethane material that was creating a different kind of capsule, and that was the reason that those implants were useful in the treatment of these patients. Following this theory, the other companies then developed what it was call textured shell implants, in which they created a rough surface on the shell, aiming toward creating a larger capsule. However, soon it was observed that the polyurethane covering the implants was being degraded by the body, and metabolites (chemical derivatives) of the polyurethane were found in the urine of patients who had those implants. The polyurethane cover implants were rapidly banned by the FDA and the company manufacturing these implants rapidly went out of business. However, the textured implant became an interesting and, in many cases, successful way to treat breast capsular contracture complication.

Unfortunately, capsular contractures at a lower rate were developing in some patients, and studies continued to be done to that end.

Dr Carlos Spera treats the capsular contractures removing the capsule (capsulectomy procedure), and replacing the existing implant with a newer one. Overtime, Dr. Spera observed successful results independently of the kind of implant that was used in the revision surgery. The reasoning is that in these days, it was hypothesized that capsular contractures are secondary to contamination of the implant at the time of insertion, with bacteria that are not in sufficient quantity, or are not aggressive enough, to produce a real clinical infection, which obviously would result in rejection of the implant. These subclinical infections appear to form what is called a “biofilm,” in which the bacteria gets walled off or isolated from the body immune system. So these bacteria inside the capsule are not treatable with antibiotics, nor are they defeated by the new system of the patient, creating this thick scar tissue around the implant, resulting in what is clinically noted as a capsule. However, even though this is the latest and most accepted theory, studies have been done trying to isolate bacteria from the capsules of patients who have undergone revision surgeries. In one of the latest studies, all available techniques to detect the presence of bacteria were utilized, and of approximately 80 specimens (i.e. capsules), bacteria were proven to exist in only 2. So the reason for formation of the capsule obviously could be multifactorial.

SO THE QUESTION IS WHAT IS THE TREATMENT THAT DR. CARLOS SPERA CAN OFFER HIS PATIENTS?

The simplest and surest solution that Dr. Spera can offer to his patients is just to remove the implants. Unfortunately, this is not always possible because a patient who has had implants placed for the treatment of true hypomastia feels very frustrated when she is unable to correct the congenital malformation (i.e. a female who lacks breasts).

Removal of the capsule and insertion of a new implant. By removing the capsule and by using a new, sterile new implant, Dr. Spera decreases the chances that bacteria are left in the pocket and or colonizing the implant.

Dr. Spera believes the use of textured silicone implants is to be considered and if the patient has no objection to that, a silicone textured implant will offer the patient something different, and it will not be “more of the same.”

Definitely if the implants have been placed on top of the muscle, Dr. Spera places them under the muscle in a new pocket to decrease the chances of developing another capsule.

If the implants are under the muscle, Dr. Spera suggests to his patients the placements of them on top of the muscle but under the fascia, a new technique called sub-fascial insertion of the implant.

It is important to note that the consistency of the original implant gel was more of a liquid. The consistency of the gel these days is called cohesive, which is why people have dubbed them “Gummy Bear” implants. The chances of the gel leaching through the shell of the implant and irritating the tissue are now less. However, since this kind of implant has been available on the American market for a relatively short time, Dr. Spera thinks time will tell if there will be any different results as far as prevention of capsular contracture.

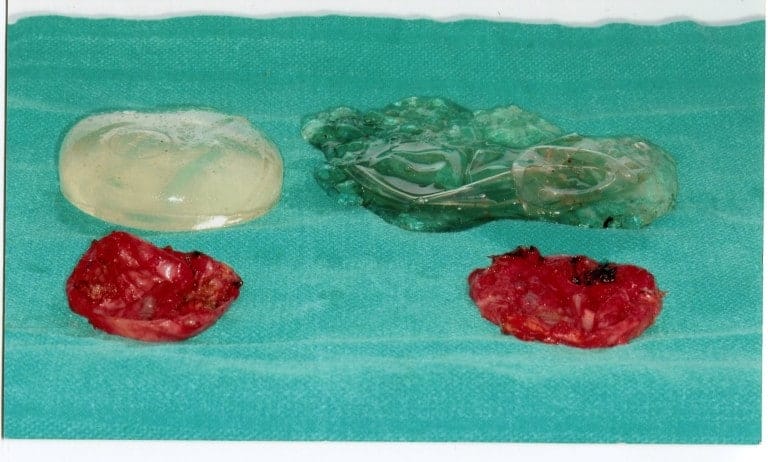

Going into clinical cases, Dr. Carlos Spera is presenting patients who develop different problems and obviously need and receive different treatments. This first patient is a 60-year-old female who underwent a breast augmentation 30 years ago with a first-generation silicone implant. In Dr. Spera experience, those implants never lasted more than 10-15 years before the shell broke, the silicone leaked out into the pocket and even migrated to the lymph nodes, and patient developed severe deformity. Many patients with this type of implant suffered stretching of the skin that required not only removal of the capsule and change of the implant, but also a mastopexy procedure (a procedure commonly referred to as a breast lift). In the picture presented, you can see the implants totally destroyed and the thick capsules that the developed in this patient’s body, in response to the aggression and irritation produced by the silicone gel.

Another case, that Dr. Spera is presenting a patient with simpler problem. She presented with bilateral displacement, pain and hardening of the implants. There was no stretching of the skin, so Dr. Spera treated this patient with capsulectomy (removal of the capsules) and exchanging the implants. In this particular patient, the implants were found to be broken. They also presented with what is called a double capsule, which is one thin capsule that is in contact with the implant, and a second layer of thickened capsule, which is the one producing constriction and hardening of the implant. For Dr. Spera, very important is the use of Bacitracin or other antibiotic solution together with the profuse washing of the pocket in order to remove any possible bacteria and prevent, in that way, recurrence of the capsule. The use of postoperative antibiotics is controversial. Most of the studies suggest that no difference is observed, in large series, between patients who take antibiotics after surgery and those who don’t.

These days, as a matter of routine, Dr. Spera’s patients undergoing any kind of surgery receive a dose of antibiotics before surgery, 30 minutes prior to the making of the initial skin incision.

Another case, that Dr. Spera is presenting a patient with simpler problem. She presented with bilateral displacement, pain and hardening of the implants. There was no stretching of the skin, so Dr. Spera treated this patient with capsulectomy (removal of the capsules) and exchanging the implants. In this particular patient, the implants were found to be broken. They also presented with what is called a double capsule, which is one thin capsule that is in contact with the implant, and a second layer of thickened capsule, which is the one producing constriction and hardening of the implant. For Dr. Spera, very important is the use of Bacitracin or other antibiotic solution together with the profuse washing of the pocket in order to remove any possible bacteria and prevent, in that way, recurrence of the capsule. The use of postoperative antibiotics is controversial. Most of the studies suggest that no difference is observed, in large series, between patients who take antibiotics after surgery and those who don’t.

These days, as a matter of routine, Dr. Spera’s patients undergoing any kind of surgery receive a dose of antibiotics before surgery, 30 minutes prior to the making of the initial skin incision.

This third and last case presented by Dr. Spera, shows a patient who underwent a breast augmentation with saline implants under the muscle. Shortly after the surgery she developed the deformities that you see in this photo. Although the breasts remained soft, the right breast displaced laterally, while the left breast moved in an upward direction because it developed a thick capsule. Dr. Spera chose for this patient chosen to perform a secondary breast augmentation and to change from the submuscular plane to the new subfascial plane. Dr Spera also switched from saline to silicone implants, which are better tolerated in that location. Two months after the second surgery, the patient’s aesthetics had improved remarkably. The deformities had disappeared, and Dr. Spera can say that the patient is now happy and the results are exceptional.

This third and last case presented by Dr. Spera, shows a patient who underwent a breast augmentation with saline implants under the muscle. Shortly after the surgery she developed the deformities that you see in this photo. Although the breasts remained soft, the right breast displaced laterally, while the left breast moved in an upward direction because it developed a thick capsule. Dr. Spera chose for this patient chosen to perform a secondary breast augmentation and to change from the submuscular plane to the new subfascial plane. Dr Spera also switched from saline to silicone implants, which are better tolerated in that location. Two months after the second surgery, the patient’s aesthetics had improved remarkably. The deformities had disappeared, and Dr. Spera can say that the patient is now happy and the results are exceptional.

Finally, there are other newly-developed implants that are called Cohesive III. One of these is called Memory Shape, meaning that the implant has memory and does not change shape with changes in position of the patient (lying, standing). They are manufactured in a contoured tear-drop shaped design, being flatter on top and with graduated projection toward the bottom. These implants are hard to palpation. Dr. Carlos Spera uses them for specific indications in reconstruction or secondary cases. In Dr. Spera’s practice, these implants are reserved for special patients since they are very firm, and some patients complain that although they look natural, they don’t feel natural, and patients are not extremely happy with these Memory Shape implants.

The silicone implants Dr. Spera uses now are called Memory Gel implants. These have Cohesive II gel, and you can actually slice through them and the silicone will not go anywhere, so they are safe even if they break. They feel slightly softer and more natural to the touch. The FDA recommends that a patient with Cohesive II implants have an MRI every 3 years to confirm that the implants are intact and have not ruptured. Dr. Spera indicates this kind of implant in thin patient and/or a patient who cannot “mask” a saline implant because her tissues are not thick enough. In Dr. Carlos Spera’s personal opinion, most patients who undergo procedures that involve breast reduction combined with augmentation have enough tissue to pad a saline implant, and there is no difference in the results, either esthetically or by palpation.

Dr. Carlos Spera thinks that breast surgery is one of the most challenging surgeries that we perform. Revisions and secondary breast surgeries are even more challenging. Complications from these surgeries can be devastating, so care should be taken when choosing the surgeon who will perform the procedure.

Finally, there are other newly-developed implants that are called Cohesive III. One of these is called Memory Shape, meaning that the implant has memory and does not change shape with changes in position of the patient (lying, standing). They are manufactured in a contoured tear-drop shaped design, being flatter on top and with graduated projection toward the bottom. These implants are hard to palpation. Dr. Carlos Spera uses them for specific indications in reconstruction or secondary cases. In Dr. Spera’s practice, these implants are reserved for special patients since they are very firm, and some patients complain that although they look natural, they don’t feel natural, and patients are not extremely happy with these Memory Shape implants.

The silicone implants Dr. Spera uses now are called Memory Gel implants. These have Cohesive II gel, and you can actually slice through them and the silicone will not go anywhere, so they are safe even if they break. They feel slightly softer and more natural to the touch. The FDA recommends that a patient with Cohesive II implants have an MRI every 3 years to confirm that the implants are intact and have not ruptured. Dr. Spera indicates this kind of implant in thin patient and/or a patient who cannot “mask” a saline implant because her tissues are not thick enough. In Dr. Carlos Spera’s personal opinion, most patients who undergo procedures that involve breast reduction combined with augmentation have enough tissue to pad a saline implant, and there is no difference in the results, either esthetically or by palpation.

Dr. Carlos Spera thinks that breast surgery is one of the most challenging surgeries that we perform. Revisions and secondary breast surgeries are even more challenging. Complications from these surgeries can be devastating, so care should be taken when choosing the surgeon who will perform the procedure.

Another case, that Dr. Spera is presenting a patient with simpler problem. She presented with bilateral displacement, pain and hardening of the implants. There was no stretching of the skin, so Dr. Spera treated this patient with capsulectomy (removal of the capsules) and exchanging the implants. In this particular patient, the implants were found to be broken. They also presented with what is called a double capsule, which is one thin capsule that is in contact with the implant, and a second layer of thickened capsule, which is the one producing constriction and hardening of the implant. For Dr. Spera, very important is the use of Bacitracin or other antibiotic solution together with the profuse washing of the pocket in order to remove any possible bacteria and prevent, in that way, recurrence of the capsule. The use of postoperative antibiotics is controversial. Most of the studies suggest that no difference is observed, in large series, between patients who take antibiotics after surgery and those who don’t.

These days, as a matter of routine, Dr. Spera’s patients undergoing any kind of surgery receive a dose of antibiotics before surgery, 30 minutes prior to the making of the initial skin incision.

Another case, that Dr. Spera is presenting a patient with simpler problem. She presented with bilateral displacement, pain and hardening of the implants. There was no stretching of the skin, so Dr. Spera treated this patient with capsulectomy (removal of the capsules) and exchanging the implants. In this particular patient, the implants were found to be broken. They also presented with what is called a double capsule, which is one thin capsule that is in contact with the implant, and a second layer of thickened capsule, which is the one producing constriction and hardening of the implant. For Dr. Spera, very important is the use of Bacitracin or other antibiotic solution together with the profuse washing of the pocket in order to remove any possible bacteria and prevent, in that way, recurrence of the capsule. The use of postoperative antibiotics is controversial. Most of the studies suggest that no difference is observed, in large series, between patients who take antibiotics after surgery and those who don’t.

These days, as a matter of routine, Dr. Spera’s patients undergoing any kind of surgery receive a dose of antibiotics before surgery, 30 minutes prior to the making of the initial skin incision.

This third and last case presented by Dr. Spera, shows a patient who underwent a breast augmentation with saline implants under the muscle. Shortly after the surgery she developed the deformities that you see in this photo. Although the breasts remained soft, the right breast displaced laterally, while the left breast moved in an upward direction because it developed a thick capsule. Dr. Spera chose for this patient chosen to perform a secondary breast augmentation and to change from the submuscular plane to the new subfascial plane. Dr Spera also switched from saline to silicone implants, which are better tolerated in that location. Two months after the second surgery, the patient’s aesthetics had improved remarkably. The deformities had disappeared, and Dr. Spera can say that the patient is now happy and the results are exceptional.

This third and last case presented by Dr. Spera, shows a patient who underwent a breast augmentation with saline implants under the muscle. Shortly after the surgery she developed the deformities that you see in this photo. Although the breasts remained soft, the right breast displaced laterally, while the left breast moved in an upward direction because it developed a thick capsule. Dr. Spera chose for this patient chosen to perform a secondary breast augmentation and to change from the submuscular plane to the new subfascial plane. Dr Spera also switched from saline to silicone implants, which are better tolerated in that location. Two months after the second surgery, the patient’s aesthetics had improved remarkably. The deformities had disappeared, and Dr. Spera can say that the patient is now happy and the results are exceptional.

Finally, there are other newly-developed implants that are called Cohesive III. One of these is called Memory Shape, meaning that the implant has memory and does not change shape with changes in position of the patient (lying, standing). They are manufactured in a contoured tear-drop shaped design, being flatter on top and with graduated projection toward the bottom. These implants are hard to palpation. Dr. Carlos Spera uses them for specific indications in reconstruction or secondary cases. In Dr. Spera’s practice, these implants are reserved for special patients since they are very firm, and some patients complain that although they look natural, they don’t feel natural, and patients are not extremely happy with these Memory Shape implants.

The silicone implants Dr. Spera uses now are called Memory Gel implants. These have Cohesive II gel, and you can actually slice through them and the silicone will not go anywhere, so they are safe even if they break. They feel slightly softer and more natural to the touch. The FDA recommends that a patient with Cohesive II implants have an MRI every 3 years to confirm that the implants are intact and have not ruptured. Dr. Spera indicates this kind of implant in thin patient and/or a patient who cannot “mask” a saline implant because her tissues are not thick enough. In Dr. Carlos Spera’s personal opinion, most patients who undergo procedures that involve breast reduction combined with augmentation have enough tissue to pad a saline implant, and there is no difference in the results, either esthetically or by palpation.

Dr. Carlos Spera thinks that breast surgery is one of the most challenging surgeries that we perform. Revisions and secondary breast surgeries are even more challenging. Complications from these surgeries can be devastating, so care should be taken when choosing the surgeon who will perform the procedure.

Finally, there are other newly-developed implants that are called Cohesive III. One of these is called Memory Shape, meaning that the implant has memory and does not change shape with changes in position of the patient (lying, standing). They are manufactured in a contoured tear-drop shaped design, being flatter on top and with graduated projection toward the bottom. These implants are hard to palpation. Dr. Carlos Spera uses them for specific indications in reconstruction or secondary cases. In Dr. Spera’s practice, these implants are reserved for special patients since they are very firm, and some patients complain that although they look natural, they don’t feel natural, and patients are not extremely happy with these Memory Shape implants.

The silicone implants Dr. Spera uses now are called Memory Gel implants. These have Cohesive II gel, and you can actually slice through them and the silicone will not go anywhere, so they are safe even if they break. They feel slightly softer and more natural to the touch. The FDA recommends that a patient with Cohesive II implants have an MRI every 3 years to confirm that the implants are intact and have not ruptured. Dr. Spera indicates this kind of implant in thin patient and/or a patient who cannot “mask” a saline implant because her tissues are not thick enough. In Dr. Carlos Spera’s personal opinion, most patients who undergo procedures that involve breast reduction combined with augmentation have enough tissue to pad a saline implant, and there is no difference in the results, either esthetically or by palpation.

Dr. Carlos Spera thinks that breast surgery is one of the most challenging surgeries that we perform. Revisions and secondary breast surgeries are even more challenging. Complications from these surgeries can be devastating, so care should be taken when choosing the surgeon who will perform the procedure.